Art Critic Reviews and other Media Coverage for Rick Williams' exhibits:

The Ravages of Addiction at Casa de Arte

by Jack Foran

Addiction can be funny, as long as it’s not us. Even if that requires a substantial dollop of denial on our part. Fortunately, most of us are really good at denial. So a lot of the artworks in the current exhibit at the Casa de Arte, on addiction, come across as funny.

(Maybe the funniest addiction set piece I know is the short section beginning on page 17 of David Foster Wallace’s novel Infinite Jest, his brilliant, unreadable treatise narrative about addiction and related obsessiveness, about which subjects he establishes his nonpareil expertise, no doubt based significantly on personal experience. Of course, David Foster Wallace wound up tragically and most gruesomely killing himself. Ultimately, these matters are not funny, they’re deadly serious.)

The funniest piece in the Casa de Arte show is a looping video by Rick Williams that precisely translates the Sisyphus myth into a superbly Allentown context. I’ve seen this piece before at the Casa de Arte when the gallery first opened, and if it required a special topic show to reprise it, it was worth it. Worth the price of admission, one could say, except that that might seem a backhanded compliment, since admission to the gallery is free. But it’s a great funny (and sad) piece.

Meanwhile, a Rick Williams installation piece presents a single-room walk-up living space of someone well along the road to rock bottom. The central furnishing, serving as a bed, is a liberally stained box-spring, amid numerous empty or half-empty alcoholic beverage containers—cans and bottles—assorted mood-adjustment pills—reds and whites—an AA handbook, a makeshift bong, a vintage TV with improvised antenna of wire coat hanger and tin foil, and an impressive stack of mail—for the most part unpaid bills, it looks like. For food, a loaf of sandwich white bread about to go moldy, some cans of pork and beans, or just beans, and several packs of ramen noodles. Wall hangings include a gaudy ceramic crucifix and a Janis Joplin Rolling Stone cover poster.

The addiction exhibit continues through September 9. In addition to the addiction exhibit, the front gallery has on display a more permanent collection of paintings and sculptures and sundries from Mexico, particularly Cuernavaca.

Double click for full review with photos: https://issuu.com/dailypublic.com/docs/thepublic81215 Page 7

Buffalo artist presents a jarring look at mental illness

Artist Rick WIlliams stands between his artwork "Behind the Curtain: Depression" and "The Well Heeled Drunk (with Nod to Manet)" in the Casa De Arte art gallery on Wednesday, Aug. 12, 2015. (Harry Scull Jr/Buffalo News)

By Colin Dabkowski

Published August 14, 2015|Updated June 7, 2016

·

Richard Williams has a hunch that everyone is mentally ill.

“It’s just a question of degrees,” he said on Tuesday morning in the large main gallery of Casa de Arte, an Elmwood Avenue art space he opened with his wife, Mara Odette Gurrero, in 2011. The gallery, partially housed in a former garage, contains dozens of Williams’ paintings and sculptural installations, each one a meditation on a different mental illness.

The show, “Infinitely Complex,” is a sprawling and sometimes jarring look into the murky subject of mental illness. It is motivated by a desire to remove the stigma that still clings like shrink wrap even to garden variety mental disorders, to argue against reducing complex people to one-dimensional diagnoses and to encourage a wider understanding and conversation about the silent suffering of so many. It runs through Aug. 20, with receptions slated for 6 to 10 p.m. Friday and 2 to 6 p.m. Sunday.

A series of tall pieces on the gallery’s east wall, based on a famous historical paintings by Velasquez, Watteau and others, testify to the ravages of schizophrenia, alcoholism and depression. Williams creates the pieces by applying oil paint directly to a mirror, and then strategically shattering the surface of the mirror. He then covers the paintings with transparent Plexiglass wrapped in its original blue film and further shrouds that sheet of intricately laced blue fabric.

“In trying to diagnose these disorders, there’s always this blue smoke and mirrors aspect to it. You don’t often get an accurate history, particularly when you’re talking about alcoholics and drug addicts,” he said. “So in order to find out what’s really going on, you have to put somebody in the hospital and defog them for a while.”

On another wall, sandwiched between abstract paintings of the big bang and oil-on-glass portraits of fractured faces in weathered antique frames from Amvets, is a 45-second video loop of Williams writing on a soiled mattress surrounded by bottles of booze and making intermittent screams that echo through the gallery.

“I’ve seen it from both ends: I’ve treated it, and I had it once myself,” Williams said. “It’s pretty accurate. That’s what it looks like.”

Near an installation of presidential portraits – “Some of these guys were sicker than others,” he said. “Richard Nixon comes to mind.” – two other videos are on view. One is a black-and-white loop of a man pushing a shopping cart filled with empty cans and bottles endlessly up the gradual incline of “Elmwood Avenue.” Another is the life story of an addict told in reverse, from his untimely death to his happier childhood, that Williams made several years ago as a warning to his son about the destructive path he was on.

Williams has seen mental illness from an uncommon variety of perspectives. He slipped into alcoholism as a teenager in South Buffalo, where his social life, he said, “revolved around the tavern.” He volunteered to go to Vietnam and served as a medic, wishfully thinking that a change in geography would put some distance between him and his alcoholism. It didn’t.

On his return, Williams worked as a physician’s assistant in a New York City prison and rehab center, where he came face to face with almost every imaginable strain of mental illness even while battling his own demons. Unsatisfied with his limited career options in the field, he went to law school in New Orleans and later became a lawyer and a judge working almost exclusively on cases involving physical and mental disabilities.

When he finally came to terms with his alcoholism, as is so often the case, depression crept in. But, he said, when he was sober, he didn’t hesitate to ask for the help he needed.

“From my standpoint, any of these mental disorders has the moral equivalence of having diabetes, and I’m including alcoholism and drug addiction: You treat it,” he said. “And so often, people are untreated. So that’s certainly one of the points. It’s very common. It’s in all families. We all know somebody, and most of us know somebody that’s not getting help.”

Since the show opened in mid-July, Williams said, visitors have stopped to tell him how powerful they found his work. He suspects many of those visitors have been dealing with their own mental health issues, and hopes that the show may encourage people to seek the help they need.

For his own part, funneling his concerns and frustrations into paintings and sculptures has been an important part of his own recovery.

“I’m a recovering alcoholic. I’ve struggled with depression as an alcoholic, I know better than anybody what my story is, what happens when I drink. And yet, it can still look awfully good to me,” he said. “Working with this subject matter is therapeutic.”

One big upside of Williams’ therapy is that so many others can benefit from it. The faces hidden behind lace and Plexiglass that line the walls of Casa de Arte each tell a story far more complex than our simplistic cultural notions about mental illnesses seem to allow.

“If you take an alcoholic, that’s not all that he is or she is. There’s a whole life there,” he said. “You can have an alcoholic who was a father, raised a family, worked, did many things well. So it’s not just all this person is.”

email: [email protected]

Colin Dabkowski– Colin Dabkowski is a digital editor for The Buffalo

News. Before that, he was The News' arts critic, responsible for covering visual art and theater in Western New York.

Infinitely Complex: Rick Williams at Casa de Arte

by Jack Foran

Aug. 11, 2015

Double click for article with color photos: http://www.dailypublic.com/articles/08112015/infinitely-complex-rick-williams-casa-de-arte

The Rick Williams art exhibit at Casa de Arte is entitled Infinitely Complex. It is interspersed with images of the cosmos. Night sky black with myriad color specks of what might be planets, stars, solar systems, galaxies. The cosmos images function as background to his even more complex real subject, the human brain.

The work is about brokenness—as that term is used to describe the human condition—and healing of the brokenness. Or not. Strategies of denial and temporizing to avoid recognition of the brokenness. And sometimes fatal consequences of such strategies.

The artwork reflects Williams’s experience as a MASH corpsman in Vietnam, then working in a Veterans Administration hospital psychiatric ward, then as a lawyer and judge adjudicating cases involving physical and mental disorders, as well as his personal struggles against similar such demons. “I’ve seen mental illness from every perspective,” he says.

Many of the paintings are on glass mirrors—usually shattered—overlain with clear Plexiglas and a blue film coating that obscures but does not completely conceal the paintings underneath, as well as holds the shards of broken mirror in place. The idea with the mirrors seems to be that the painter as he paints sees himself in the painting. (Indeed, as Williams told me when I viewed the show, several of the paintings are self-portraits. It is hard to perceive this without being informed of it, due to the obscuring effect of the blue film overlay.) The idea with the shattered mirrors is the existential brokenness idea.

Another idea with the blue film overlay seems to be about how we mask and obscure the brokenness. The denial and temporizing. With alcohol, drugs, whatever addictive substances or practices.

This is not pretty picture art. Among the paintings and several sculptural works are some videos. One showing the artist—no blue film overlay here—in the throes of delirium tremens. Williams said this was a staged performance, not the real thing, but that he’s been there.

And all in all as much emphasis on non-survival as survival of the mental and emotional difficulties and addictive strategies. Two sculptural pieces are essentially coffins, with Plexiglas and blue film covers. One with a barely visible—through the blue translucent cover—emaciated-looking facsimile corpse. The title of the coffin piece is Bulimia: Dead at 32. Other works refer to other medical/psychological conditions (depression, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder) and the self-destructive actions (rapid or protracted) they can lead to. A painting not under blue film overlay is entitled Juan Carlo Ruiz Morales: Untreated Depression; Death by Suicide, age 54. He looks like he could be 84. An adjacent full-length portrait of a beautiful young woman, tall and straight, is entitled Masheka Wilson, model, Death by Heroin Overdose at age 41.

In the artist’s case, early Catholic religious experience gets some of the blame. An enigmatic painting entitled Requiem for My Sexuality depicts a nude female—homage perhaps to Titian’s nude, or Goya’s, or both—and Catholic nuns in black and white habits in a line approaching the prostrate nude as if viewing a corpse at a wake. Another work—in part in homage to Dali—is a large crucifix with a double strand of hemp rope in the Christ role.

Another video is called Mario T: Death of an Addict. Actually, not quite death, almost death, Williams explained. A video slide show of photos of his son, he said, proceeding backwards from his young adulthood and what looks like drug and alcohol and attitude problems, to childhood sweet innocence. How did it happen? Part of the answer, it seems, we pass things along.

Another concurrent theme is Williams’s lifelong devotion to the study and practice of art. Several of the paintings under Plexiglas and blue film are self-portrait remakes of some iconic paintings of the Western tradition. Watteau’s Pierrot, Manet’s Absinthe Drinker. Some of these works are further obscured by a further overlay of a black lace fabric.

The exhibit continues through August 16. A reception is scheduled for August 16, 2-6 pm.

Rick Williams at The National Veteran's Art Museum in Chicago (formerly Vietnam Veterans Art Museum): http://www.thegatenewspaper.com/2013/11/national-veterans-art-museum-celebrates-first-anniversary-in-new-location-exhibits-veterans-art/

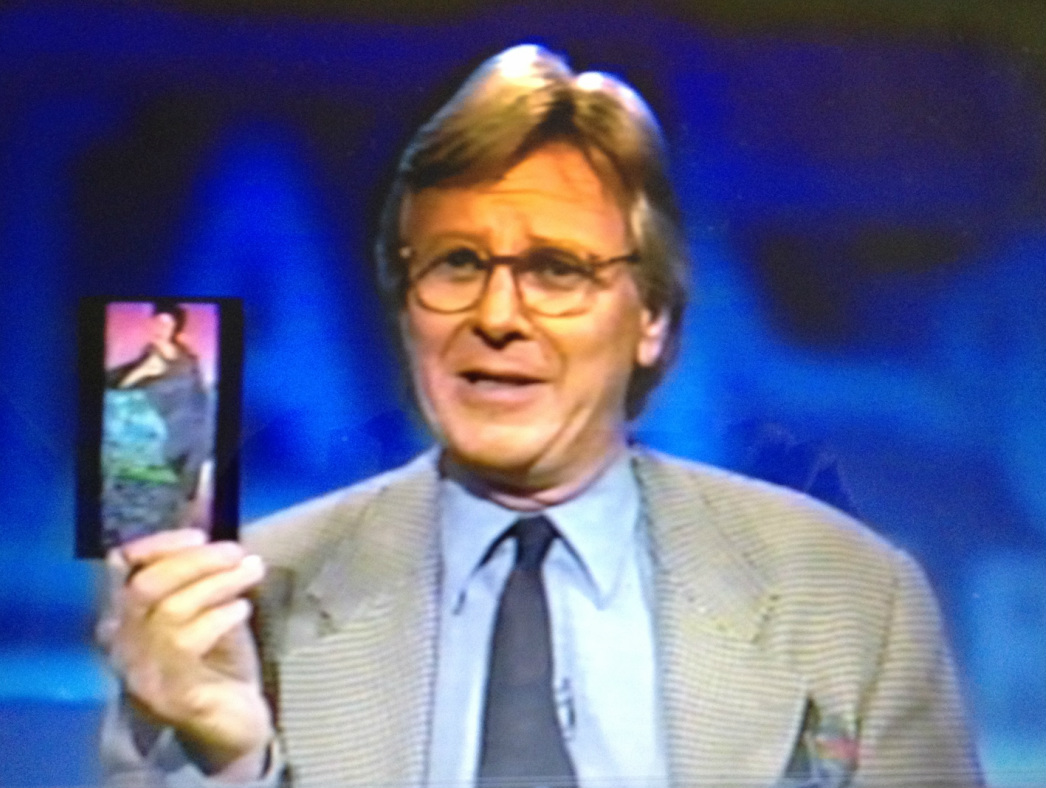

WETA's "Around the Town" with art critic Bill Dunlap recommending Rick's exhibit "The Cone Sisters and their Friends"

At Casa de Arte, a Meditation on War, Its Suffering, Its Uselessness

by Jack Foran

Sep. 26, 2017

“It is the Revolution, the magical word that is going to change everything, that is going to bring us immense delight and a quick death.” —Octavio Paz

The antepenultimate exhibit at Casa de Arte on Elmwood in Allentown is entitled The Glorious Revolution! For Whom? Two more exhibits then, and closure of the gallery, which has been operated for the last seven years by life partners and fellow artists Rick Williams and Mara Odette. And “no regrets,” Williams says of the gallery experience.

Around the period when attention in this country was focused on the so-called Great War in Europe, Mexico fought a Revolutionary War of such general carnage—amid a dizzying array of changing alliances and regular assassinations of political and military leaders, but comparatively slight resultant change of conditions for the poorest and most oppressed Mexicans—as to raise the title question. Para quien? For whom?

It’s Williams’s question, and the exhibit comprises his skeptical response. Learning about the period, he said, “What struck me was the amount and extent of the bloodshed. Out of a total population of 15 million, 1.5 million died. Ten percent of the entire populace. Plus incalculable numbers of wounded and displaced. And did it do any good?”

(His skeptical attitude may apply to war in general. Williams was a medic during the Vietnam War and subsequently worked with veterans, including in a VA hospital. So he has seen his share of actual carnage, and observed the human toll versus political and social and economic actual results of armed conflict.)

Responses to the question by some Mexicans are presented in video interviews in which Williams asked them, are things better now than they were before the revolution? One old woman interviewee answered, “A little better.” A man who was a grand-nephew of General Emiliano Zapata—probably the purest of the revolutionaries, most true to the goal of land reform to alleviate the abject conditions of the campesinos—thought conditions were “much better.”

Other works include photos related to the revolution, some from various Mexican sources—including museums—others of Williams’s own making in the course of his and Odette’s sojourns in Mexico—she is originally from Mexico and they live in Mexico half the year—and others from the internet. The most impressive are posed photos of actual revolutionaries, well-armed and ammunitioned. One of a young woman fighter, another of a boy who couldn’t be more than about twelve. Some of the photos are greatly enlarged and overlaid with a translucent blue material to produce “a kind of distancing effect,” according to Williams.

A major work in the show is a triptych of video imagery of three key figures in the revolution—Zapata, Francisco I. Madero, duly elected President of Mexico, presiding from 1911 until he was assassinated in 1914, and the celebrated Pancho Villa—along with abstract paintings by Williams—black panels with a few minimalistic stripes or slashes of color, predominantly red, white, and green, the colors of the Mexican flag—recapitulating central visual motifs of the video imagery—and little shrine altars featuring dress items and accoutrements visible in the video portraits—sombreros for Zapata and Villa, a formal high hat and white gloves for Madero. Williams particularly admires Zapata, to a lesser extent, it seems, Madero, and least of all Villa.

And in the center of the room, a Christian cross arrangement of five coffins draped with a Mexican flag. For the 1.5 million.

The Mexican Revolution exhibit continues through October 1.

The final Casa de Arte offering, November 1-15, is the gallery traditional Dia de los Muertos exhibit.

For article with photos: http://www.dailypublic.com/articles/09212017/casa-de-arte-meditation-war-its-suffering-its-uselessness

At Casa de Arte, a Meditation on War, Its Suffering, Its Uselessness

by Jack Foran

Sep. 26, 2017

“It is the Revolution, the magical word that is going to change everything, that is going to bring us immense delight and a quick death.” —Octavio Paz

The antepenultimate exhibit at Casa de Arte on Elmwood in Allentown is entitled The Glorious Revolution! For Whom? Two more exhibits then, and closure of the gallery, which has been operated for the last seven years by life partners and fellow artists Rick Williams and Mara Odette. And “no regrets,” Williams says of the gallery experience.

Around the period when attention in this country was focused on the so-called Great War in Europe, Mexico fought a Revolutionary War of such general carnage—amid a dizzying array of changing alliances and regular assassinations of political and military leaders, but comparatively slight resultant change of conditions for the poorest and most oppressed Mexicans—as to raise the title question. Para quien? For whom?

It’s Williams’s question, and the exhibit comprises his skeptical response. Learning about the period, he said, “What struck me was the amount and extent of the bloodshed. Out of a total population of 15 million, 1.5 million died. Ten percent of the entire populace. Plus incalculable numbers of wounded and displaced. And did it do any good?”

(His skeptical attitude may apply to war in general. Williams was a medic during the Vietnam War and subsequently worked with veterans, including in a VA hospital. So he has seen his share of actual carnage, and observed the human toll versus political and social and economic actual results of armed conflict.)

Responses to the question by some Mexicans are presented in video interviews in which Williams asked them, are things better now than they were before the revolution? One old woman interviewee answered, “A little better.” A man who was a grand-nephew of General Emiliano Zapata—probably the purest of the revolutionaries, most true to the goal of land reform to alleviate the abject conditions of the campesinos—thought conditions were “much better.”

Other works include photos related to the revolution, some from various Mexican sources—including museums—others of Williams’s own making in the course of his and Odette’s sojourns in Mexico—she is originally from Mexico and they live in Mexico half the year—and others from the internet. The most impressive are posed photos of actual revolutionaries, well-armed and ammunitioned. One of a young woman fighter, another of a boy who couldn’t be more than about twelve. Some of the photos are greatly enlarged and overlaid with a translucent blue material to produce “a kind of distancing effect,” according to Williams.

A major work in the show is a triptych of video imagery of three key figures in the revolution—Zapata, Francisco I. Madero, duly elected President of Mexico, presiding from 1911 until he was assassinated in 1914, and the celebrated Pancho Villa—along with abstract paintings by Williams—black panels with a few minimalistic stripes or slashes of color, predominantly red, white, and green, the colors of the Mexican flag—recapitulating central visual motifs of the video imagery—and little shrine altars featuring dress items and accoutrements visible in the video portraits—sombreros for Zapata and Villa, a formal high hat and white gloves for Madero. Williams particularly admires Zapata, to a lesser extent, it seems, Madero, and least of all Villa.

And in the center of the room, a Christian cross arrangement of five coffins draped with a Mexican flag. For the 1.5 million.

The Mexican Revolution exhibit continues through October 1.

The final Casa de Arte offering, November 1-15, is the gallery traditional Dia de los Muertos exhibit.

For article with photos: http://www.dailypublic.com/articles/09212017/casa-de-arte-meditation-war-its-suffering-its-uselessness